Otto Hitzberger

Born in Munich in 1904, Otto Georg Hitzberger spent part of his boyhood with an uncle in the desert of Namibia, then in the German colony of Southwest Africa – nearly as distant from the Bavarian mountain culture of his birth as it is possible to go. At 15 he entered the renowned woodcarving school in Oberammergau where he developed his fundamental skill as a carver of wood.

Born in Munich in 1904, Otto Georg Hitzberger spent part of his boyhood with an uncle in the desert of Namibia, then in the German colony of Southwest Africa – nearly as distant from the Bavarian mountain culture of his birth as it is possible to go. At 15 he entered the renowned woodcarving school in Oberammergau where he developed his fundamental skill as a carver of wood. After advancing to the Academy of Fine Arts in Berlin, Hitzberger absorbed a knowledge of artistic styles and techniques that allowed him to rise to the top of his profession in Europe between the World Wars. It was only after the destruction of his large Berlin studio in 1944, and his subsequent flight from the collapse of the Third Reich, that he sought and found his own vision as an independent artist.

Hitzberger moved to the United States in 1949, settling first in Manhattan – the lodestar of many artists fleeing the chaos of Europe – but soon moving upstate to Syracuse, New York for a job in a carving studio that was much like his former Berlin atelier. Religious carvings from this brief period of his American career can be found in churches and public buildings in the Eastern U.S.

Washington Depot, Connecticut was Hitzberger’s next work site, and it was there where he first seriously began to pursue his career as an independent sculptor. In 1956, he moved west for a stay in Sausalito, California interspersed with long work visits to Taos, New Mexico. Three years later – with his wife Catherine, whose influence on his artistic life was crucial – he went to live and work in the tiny port of Fuengirola on the Andalusian coast of Spain. During this time he spent periods working each summer near Innsbruck, Austria, in the same kind of Alpine environment as his family home in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, just across the Tyrolean border.

In 1964 Otto and Catherine designed and built their ideal house and studio, with solar panels and a water system using the old Moorish irrigation channels that course down the slopes of the Sierra de Mijas, west of Málaga. They had views of the sea narrowing to the Strait of Gibraltar and, weather permitting, of the Moroccan coast. For the first time, Otto had the perfect space to display his bronzes, terracottas, and woodcarvings. He exhibited them in niches in the studio and house, on tops of walls, within the gardens and olive groves, and even on the ancient stone threshing floor near the irrigation channel that ran through the property.

Much of Hitzberger's most seminal work was done in the unique silence and cultural ambiance of Málaga and the Sierra de Mijas. But after the demise of Franco, the splendid isolation that had proved so valuable to his work became problematic. Changes in foreign residence requirements and increased crime forced the artist to contemplate a return to America after a quarter-century's absence. In 1982 Otto and Catherine moved to a house in the Tanque Verde section of Tucson, Arizona, where he built his studio in what had been a garage.

Among the saguaros of the house's grounds, his sculptures found still another fine home.

Hitzberger frequently referred to the two desert experiences of his life – both in his work and in conversation. And it was in the clean brilliance of the Sonoran desert that he rediscovered the freedom of his American life. But after four-and-a-half years, the extreme summer heat and desert isolation compelled the Hitzbergers to move to a mountain above Boyes Hot Springs, outside of Sonoma, California, in 1987.

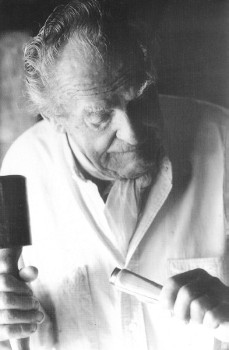

It was there that Hitzberger's American exhibitions, his international reputation, and his regional fame all blossomed for well over a decade. In Sonoma he found more direct support and recognition than he had experienced since leaving his native Germany. For most of his life he had been a citizen of the world, but in this last chapter he was more accurately described as an artist of California. His painting flourished and his stone, wood, and bronze pieces continued to appear from his remarkable nonagenarian hands. He was 98 when he passed away in 2002.

Margaret Mead said that anyone born before the Second World War is "an immigrant in time," and the implications of that statement are even more profound for those very few artists who were born before World War I and continued to work long after World War II. Otto Hitzberger was most probably the last of his breed of highly trained, well-schooled, and vastly experienced master carvers who grew and evolved into master sculptors. For more than three-quarters of a century, Otto Hitzberger worked through his absolutely unique individuality to produce a body of work that is nearly unparalleled in this era.